|

| First flight of the Flyer 1, December 17, 1903, Orville piloting, Wilbur running at wingtip / Library of Congress / Public Domain |

“What had transpired that day in 1903, in the stiff winds and cold of the Outer Banks in less than two hours time, was one of the turning points in history, the beginning of change for the world far greater than any of those present could possibly have imagined. With their homemade machine, Wilbur and Orville Wright had shown without a doubt that man could fly and if the world did not yet know it, they did. Their flights that morning were the first ever in which a piloted machine took off under its own power into the air in full flight, sailed forward with no loss of speed, and landed at a point as high as that from which it started.” ~ David McCullough, The Wright Brothers

Tim and I like to listen to audiobooks when driving long distances.

The Wright Brothers by David McCullough was one of the first we heard after we began our life on the road. Their feat on that fateful day of December 17, 1903 changed the world forever and ushered us into the space age. When we finished the book, we vowed that one day we'd visit the Wrights' bicycle shop in Dayton, Ohio and the dunes at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina where their efforts came to fruition. We stopped at Kitty Hawk a year ago in

April 2017; now, as we head west on Interstate 70 towards the farm in Kansas, we stopped at Dayton for two days. That was hardly enough time to follow Dayton's Aviation Trail to the ten historical sites located in this city and nearby Wright-Patterson Air Force Base so we hit the highlights as best we could. Our first stop was the Wright Cycle Shop near the center of Dayton.

|

| The Wright Cycle Shop |

“The bicycle was proclaimed a boon to all mankind, a thing of beauty, good for the spirits, good for health and vitality, indeed one’s whole outlook on life. Doctors enthusiastically approved. One Philadelphia physician, writing in The American Journal of Obstetrics and Diseases of Women and Children, concluded from his observations that “for physical exercise for both men and women, the bicycle is one of the greatest inventions of the nineteenth century.” ~ David McCullough, The Wright Brothers

|

| Showroom of the Wright Cycle Shop |

Wilbur and Orville had a reputation in their neighborhood for being able to fix anything. Swept up in the cycling craze at the turn of the 20th century, neighbors sought them out to fix a broken bicycle chain or to straighten a wobbly bike tire. The brothers decided to capitalize on their mechanical skills by moving their flourishing printing press business at number 1127 West Third Street upstairs and opening a bicycle repair shop on the ground floor.

The least expensive bicycle Wilbur and Orville sold in 1895 cost $50, an expensive purchase at a time when wages for day laborers were less than $2000 per year. But the Wrights gave their customers every chance to own one, offering installment plans and credit for trade-ins.

“Wilbur would remark that if he were to give a young man advice on how to get ahead in life, he would say, “Pick out a good father and mother, and begin life in Ohio.” ~ David McCullough, The Wright Brothers

Perhaps it was the flying toy brought home by Bishop, their itinerate preacher father, that first sparked the boys' interest in trying to solve the age-old question of whether man could ever fly. Whatever the impetus was, it prompted Wilbur to write to the Smithsonian to ask for any papers regarding flight which the brothers avidly studied.

As bicyclists, Wilbur and Orville knew that in order to maintain balance on a bicycle in motion, one needed to be able to control it. Turning a bicycle, for example, one needed to turn the handlebars (yaw) and lean in the direction one wanted to go (roll). They intuitively realized that a flying machine would have similar requirements and that insight helped them unlock the secret of flight. Eager to try their first prototype, they boxed up their work to transport it to the Outer Banks where the winds, the soft sands and the isolation from newspaper reporters would prove to be a good location to test their flyers. Four different times they made the trip during the winter off-season, each time with a more refined machine until finally their 1903 Flyer soared with Orville aboard.

|

| 1901 glider flown by Wilbur (left) and Orville / Library of Congress / Public Domain |

"It wasn't luck that made them fly; it was hard work and common sense; they put their whole heart and soul and all their energy into an idea and they had the faith." ~ John T. Daniels, eyewitness at Kill Devil Hills

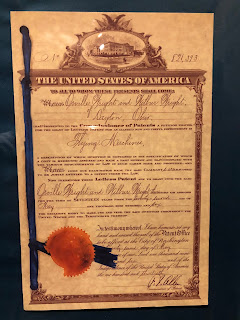

The U. S. Patent Office assigned patent No. 821,393 to the Wright brothers for their flying machine. The Smithsonian, however, did not agree that the Wrights were the first to discover flight. Instead, having granted $20,000 (another $50,000 was given by the War Department) to Smithsonian secretary Samuel Langley, the Smithsonian claimed that, despite two failed attempts when Langley's flying machines dropped like a rock into the Potomac, he was the father of flight, a claim that Orville Wright disputed until the Smithsonian retracted its opinion in 1942.

“Not incidentally, the Langley project had cost nearly $70,000, the greater part of it public money, whereas the brothers’ total expenses for everything from 1900 to 1903, including materials and travel to and from Kitty Hawk, came to a little less than $1,000, a sum paid entirely from the modest profits of their bicycle business.” ~ David McCullough, The Wright Brothers

|

| Huffman Prairie |

In 1904 the Wrights built the Flyer II. Deciding to forego the costs of the lengthy trip to Kitty Hawk, they set up an airfield at Huffman Prairie eight miles northeast of Dayton (which Tim and I found after venturing down a obscure tree-canopied, single-lane dirt road) and for the first time invited reporters to view their flying machine on its trial run, a flight that was less than stellar due to engine troubles and slack winds. So reporters turned their attention elsewhere, thus, giving the brothers the anonymity they needed to improve their machine while their competitors grabbed the spotlight.

“In no way did any of this discourage or deter Wilbur and Orville Wright, any more than the fact that they had had no college education, no formal technical training, no experience working with anyone other than themselves, no friends in high places, no financial backers, no government subsidies, and little money of their own.” ~ David McCullough, The Wright Brothers

When the brothers were finally ready to market their machine, few believed their claim that it would fly. The U.S. War Department snubbed them. Only the French military expressed an interest so once again, they boxed up their machine and Wilbur took it to France. During his first public performance there, he was aloft for only one minute and 45 seconds, but his ability to make turns and circle the airfield in figure eights thrilled the crowd.

By the end of 1909 the Wright brothers were world famous and very wealthy. Their sister Katherine who had endlessly encouraged their pursuit now recommended they build a new home where they could entertain the many notable people, including Charles Lindbergh, who came to visit them. However, Wilbur died at age forty-five of typhoid fever only a few months before Orville, their father Bishop and Katherine moved into the home on Hawthorn Street.

“Of the immediate family of 7 Hawthorn Street, only Bishop Wright had yet to fly. Nor had anyone of his age ever flown anywhere on earth. He had been with the brothers from the start, helping in every way he could, never losing faith in them or their aspirations. Now, at eighty-two, with the crowd cheering, he walked out to the starting point, where Orville, without hesitation, asked him to climb aboard. They took off, soaring over Huffman Prairie at about 350 feet for a good six minutes, during which the Bishop’s only words were, “Higher, Orville, higher!” ~ David McCullough, The Wright Brothers

|

| Hawthorn Hill |

Hawthorn Hill became a gathering place for the Wright family. When we visited Hawthorn Hill, our tour guide showed us family movie clips of holiday dinners and sledding occasions when nieces and nephews flew down the backyard hill. We also learned that Orville, although shy in public, loved practical jokes and once surprised a dinner guest with a fake cockroach that he surreptitiously pulled from underneath the guest's plate across the table. Orville suffered back pain, the result of a 1908 crash of their airplane. The carpet underneath his desk chair is still worn from the way he shuffled his feet to relieve his sciatic pain while seated.

|

| From upper left, clockwise: sleds, armchair with bookstand invention, central vacuum, shower jets |

He installed jets in his shower, a central vacuum throughout the house and a call system to summoned the housekeeper, all evidence of his life-long love of mechanical innovations. He set up a laboratory near the old bicycle shop and continued to go there each day for several hours. Some believe he carried on an affair there with his secretary Mabel Beck who is suspected of encouraging his estrangement from his sister after Katherine married in 1926.

|

| The Wrights (Wilbur, Katherine, Orville and their parents) are buried in Dayton's Woodland Cemetery. |

It was only as Katherine lay on her deathbed that Orville laid aside his feelings of abandonment and hastened to her side.

|

| Following Orville's express wishes, the 1905 Flyer is displayed at Dayton's Carillon Historical Park so visitors may see it from above. |

Meanwhile, the controversy between Orville and the Smithsonian continued to rage. In 1925 Orville announced that he would send the 1903 Flyer to the Kensington Science Museum in England unless the Smithsonian recanted its conclusion that Langley, not the Wright brothers, was the first to master flight. The Smithsonian did not revise its stance so Orville packed up the plane and shipped it to England where it remained until 1942 when the Smithsonian finally withdrew its claim. Of course, by then England was fighting the Nazis making it impossible to ship the Flyer to back to the States. When the war ended, the Flyer came home to the Smithsonian in 1948, just a few months after Orville died.

|

| Wilbur Wright and Orville Wright seated on steps of rear porch, 7 Hawthorne St., Dayton, Ohio, 1909 / Library of Congress / Public Domain |

“On July 20, 1969, when Neil Armstrong, another American born and raised in western Ohio, stepped onto the moon, he carried with him, in tribute to the Wright brothers, a small swatch of the muslin from a wing of their 1903 Flyer.” ~ David McCullough, The Wright Brothers